Establishing context

When people ask me to design a learning intervention, they often already have a solution in mind. It’s generally a fairly simple one: a workshop or an e-learning module. Sometimes they ask for blended learning, but if so, it is usually one particular format: an e-learning module followed by a facilitator-led workshop.

In one case I recall often, a project owner asked for an e-learning module that would display each page of a new policy and record whether the learners had been shown it.

One of the key things I try to bring to new projects is my ability to take a step back and look at the context, the learners, and the change the project is aiming to create, before I jump into planning learning activities or deciding on appropriate formats.

Why are we doing this?

My first step is always to ask the project owner to tell me why they see the project as necessary. Are you trying to get people to do something new, to do something differently, to stop doing something, or to keep doing something? And what do you hope this will do for the organisation? How will it help the organisation to reach it’s goals?

I do this first, before we talk about what they want made, because too much information about people’s vision of what they want can be a trap. If I think I know what the solution is, I’m already limiting my range of options. I find it’s best to get a solid grip on the goals and constraints I’m going to be dealing with, before I focus on the solution. That way, I’ll interpret everything in the light of those goals, rather than interpreting the goals so that they work in with the format.

This means that each project starts for me with listening, and with questions that go well outside ‘learning’. A successful starting point isn’t about what we think learners should know; it’s understanding the environment, the mahi (work), and how the mahi supports the goals of the organisation. Without that, any learning intervention can miss the mark.

Line of sight

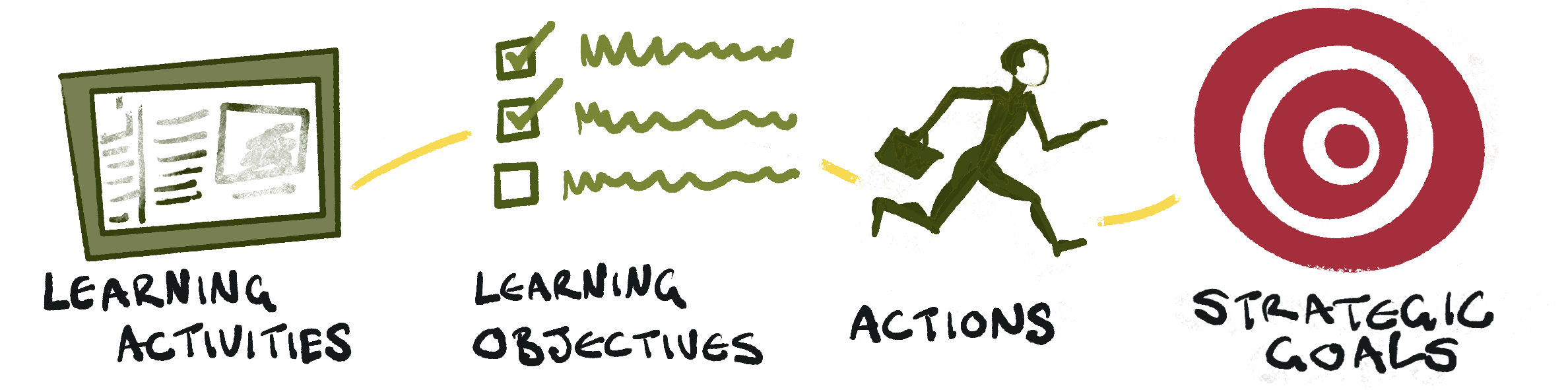

The concept of ‘line of sight’ is useful for this. It’s about creating a clear chain of linkages between what the learners are doing and the high-level goal of the learning intervention, and keeping that chain of linkages clear for everyone involved.

Just about all workplaces have an overall goal and also strategic goals that they believe will help them to reach it. Many teams have goals, and many roles.

Establishing at the start how any workplace learning activity will support these goals can both inform the activity’s design and help get the management support the learning will need to succeed.

It also helps work out how we can tell whether the learning intervention is working. Worthwhile evaluation relies on this, and it is much, much easier to do if there is an explicit statement of what the project’s stakeholders are hoping a learning intervention will achieve than if all you have is some sentences starting with verbs from Bloom’s Taxonomy. (Not to disrespect Bloom et al. here! But learning objectives aren’t usually why we are investing time and energy into learning design. They’re a tool we use to make sure our time and energy are well directed.) It’s also worth while finding out how these people intend to judge whether the whole thing has worked.

Mapping goals to behaviours

The key line of sight I try to map out is the line between the learning activities and the strategic goal that the project is there to support.

Strategic goals are affected by the actions people take: are the workers’ behaviours on the job the ones that will support the goals? So for a clear line of sight, we need to know what the target behaviours are. A really good work to read if you want to learn more on this concept is Robinson’s Performance Consulting (2006).

Actions can sometimes be supported by learning. If people don’t know how to do something, they may be able to learn to do it. Well formed learning objectives can specify what learning is required for that to happen. (Badly formed ones really don’t help with this.) This bit of the line of sight is pretty important. Not all behaviour changes can be achieved through learning, and it’s surprising how often people try to use learning activities for situations where no actual learning is required.

The third link we need to have is between the activities we design and the learning objectives. Unless it is clear how the learning activities will help the learners achieve the learning objectives, we don’t have a clear line of sight between the learning design and the strategic goals.

What solutions have already been tried?

A few years back, a client came to me and asked me to scope the development of a new e-learning module on how to use an IT system.

This was all very well, and there was a definite issue where staff were having difficulty using the system because they didn’t know how to use it. But in discussing the context, the learners, and the work, two things came out:

- A half-hour e-learning module wasn’t likely to be remembered when the learners were trying to use the system. The problems they were having with the system were not things anyone was likely to remember a month after using the module, without any practice in between. And they didn’t use the system often enough to get that practice.

- A half-hour e-learning module already existed and was available on their learning management system.

Yes, you read that right. They’d come to me to design a solution they already had, which wasn’t effective anyway.

It’s always important to ask what solutions have already been tried, so we can avoid repeating things that have already been found ineffective.

So what did we do? We looked into getting pop-ups added to the IT system, but it was too expensive. We went with an easy-to-navigate set of pages on the intranet, with a short manager-led session showing the staff where the pages were and how to find them. That way, all the staff needed to remember was that their usual source of information (the intranet) had information about the IT system. For people who wanted to be better prepared, we included a reminder about the e-learning module. The intranet pages were well received by the users, and the new solution was also easy for the internal team I was supporting to update.

Engaging the learners

People bring knowledge and experience into any learning situation, and for workplace learners, this means we need to think hard about what this means for engaging them. Adult learners are motivated by relevance and immediate application (Knowles, et al. 2005, page 67–68). If we ignore that, we lose their engagement.

I’ve seen this happen: training pitched at the wrong level leaves people switched off, even if they finish the activity. I’ve also been this learner, sitting through things I already knew, and either zoning out or (I can see now) disrupting my classmates’ learning flow by trying to move on to the next steps before they are ready. (Sorry to my ex-classmates!)

An example of this kind of error came up a few years back when I was reviewing a plan for a learning programme on high-voltage electrical safety. The learning designer had written learning objectives that included a lot of basics about electricity, things like ‘The learner will be able to explain what voltage is’. All were things that the learners definitely needed to know, to understand the programme. But all the learners were in roles where they needed to know the basics of electricity to get the job; they had electrical qualifications and used that knowledge every day. We had limited training time, and we were effectively planning to use it to teach the ABC to graduates! By focusing on the learning objectives, but not looking at the learners, or their jobs, the learning designer had missed the point badly.

Taking the time to understand not just what the desired end state is for the learners, but also their starting state can help us gain and keep engagement, and ensure that we are showing respect for the value of the learners’ time and energy.

Learners also have learning spaces, workspaces, abilities, and their own lives and goals. If we are going to teach them anything, we need to know enough about them and their motivations to plan activities that work for them.

What happens when we skip context

From my experience, missing context usually leads to three problems:

- Mismatched content: learners get training they don’t need, and gaps remain unaddressed.

- Lost trust: people don’t take learning seriously if it feels irrelevant.

- Wasted investment: organisations spend on solutions that don’t change behaviours.

I’ve seen all three, and they remind me why I always start with context.

What does this look like in practice?

For the e-learning module I mentioned at the start of this post, my investigation of context found that the organisation wanted to avoid poor publicity and ensure staff compliance with the law by having all staff follow some new rules around information management.

The learning that was needed was not actually reading the policy, but understanding what the new information management rules meant for day-to-day work that varied from team to team. The policy document was a tool designed to enable that, but not something that mattered for its own sake.

The learners were busy people, who didn’t necessarily have strong cues in their work that would lead them to see how the new policy would need to affect their actions. They worked in shared spaces with their team mates and had group activities like team meetings regularly.

The learning activities we ended up making were a long way from ‘click Next on each page of the new policy’. Instead, we made a short e-learning module teaching the purpose of the policy, with meaningful examples, and partnered it with a workshop for managers, teaching them each how to lead a scenario-based activity for their team that would help them see how the policy applied in their team members’ roles. The scenarios were pre-planned, and differed for each team to match the nature of their work.

The evaluation for this project was really positive. The opportunity to look at the new rules as teams meant each team could talk about what good practice would look like for them. The learning activities were relevant and engaging, and there was evidence of real changes in the learners’ actions on the job.

Context isn’t a box to tick at the start of a project. It’s the foundation for everything that follows. When I take time to understand organisational goals, the target changes to learner behaviour, and the realities of the learners’ work, I can design learning solutions that meet the learners where they are, and support real change.